Reflections on the Void of Revolutions

- Cianan Sheekey

- Aug 13, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 16, 2025

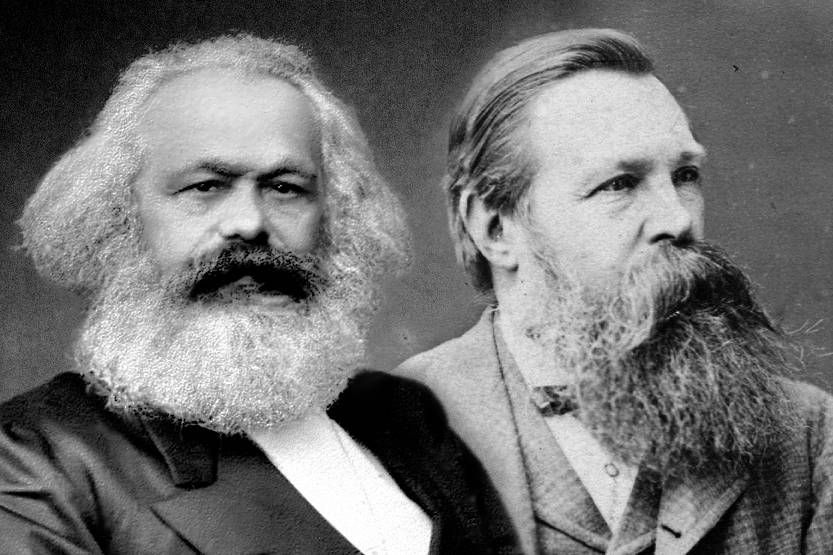

The work of Marx has endured in the minds of the scholarly and unscholarly alike since its publication; he is both the authoritative theorist of socialism and a symbolic figurehead, representing the class-conscious in their revolution against the bourgeoisie. A revolution, proposed by Marx as an inevitability, that has yet to manifest. There has been no armed conflict between the working-class proletariat and the upper classes. The rich remain uneaten, the means of production unseized, the workers of the world unorganised. In the spirit of another seminal ideologue, today we reflect - not on the French Revolution, but on the ‘inevitable’ class revolution yet to come.

This article explores the failings of Marxist theory, which posits that through awareness of class exploitation, the lower classes could, and therefore over sufficient time would, rebel against those of higher economic status. There are several issues with this vapid claim, particularly in the present day.

The idea of building class solidarity is presented within Marxism as a scientific concept, and this stance is defended with great academic vigour. Marx & Engels discussed not just a political uprising, but reached these conclusions through what they believed to be empirical study; “They looked to the process of labour, the conscious human interaction with nature, and the relations of production, as the basis of those forces”. This admirable, if peculiar, methodological approach contributes to Marxist misunderstandings of the ‘inevitability’ of class revolt.

Applying a scientific approach to Marxist ideals, however, opens the door to scientific critiques, including Karl Popper’s notion of unfalsifiability. Popper espoused the need for falsificationism, the idea that any theory needs to be open to disproof, utilising novel scientific principles to question the viability of Marxist understandings where they are not open to challenge. In The Open Society and Its Enemies, Popper argues that ad hoc theory is used to “salvage” Marxism despite its blatant retrospective inaccuracies. He went so far as to attaint Marxism as pseudo-science, as a result of these feeble attempts to self-reinstate ideological legitimacy, comparing it to astrology in a brutal but just manner.

Beyond its unfalsifiability, further issues arise within Marxism given that class is not a concept beyond the veil of the contemporary masses. The superstructure of the state cannot produce smoke of sufficient quantity or density to hide societal inequalities; the working class are deeply aware of their status and conscious of it. Yet, no mass uprising appears likely. The obvious Marxist counterargument is to refer to the work of Gramsci.

Gramsci’s work extended Marxism’s perceived economic control of lower classes to be a cultural concept, referred to as cultural hegemony. Contemporary Marxists argue that particular modern phenomena, especially social mobility, erode class consciousness and the potential for a capitalist downfall through revolution, manufacturing widespread consent for inequality-producing structures. To address this stance, we have to take a step back and evaluate the broader argument.

Supposedly, despite a collective understanding of class structures, society is constructed in such a manner that elites are never truly and collectively questioned but instead consented to en masse. Hence, knowledge of Marxist theory ought to bring a level of awareness to transcend this coercion. As the son of a glass manufacturer and till operator, I am working class by almost all definitions, and yet, despite my knowledge of the Marxist episteme, I do not wish for revolution nor tectonic shifts in modern economic systems. Gramsci’s work would suggest state superstructures have a tight grasp over me, as could be said for everyone informed of Marxist theory and yet not in favour of class war, as if we are all suffering from an unwilful ignorance. This presents a problematic assumption of self-correctness, that attempts to verify itself through the pretence that it could be correct. For any ideology that isn’t Marxism, this would prove a fatal flaw, another example of Marxist unfalsifiability that violates aforementioned Popperian criteria, highlighting how quickly we have veered into the ‘what is truth?’ dimension of political thought.

Surely, within such a line of argument, the superstructure would never allow for its exposure and the subsequent class consciousness. Yet, no efforts are made to conceal class. In the social media age, class has never been more apparent and obvious and Marxist theory dated and inaccurate. Still, credit is due for such ideological persistence. These faults could have, and perhaps should have, relegated Marxism to the dustbin of history - the same place the ideology erroneously believed capitalism would end up.

Even more symbolic (and less extreme) ballot box revolutions have proven unfruitful in recent years. In Britain, former Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn offered a return to the Party serving “as the voice of the working class” - a return that the working class electorate vehemently rejected, with only 33% of C2DE voters (manual workers, the unemployed, those living off of pensions or benefits) backing Corbyn in the 2019 General Election. Despite offering a distinct, alternative political trajectory for the lower classes, they opted to pledge their allegiance instead to Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, the same entity that at the start of the decade had engaged in an austerity run on the public sector apathetic to working interests. The defeat marked a failure in anti-establishmentism. The offers of an atypical politician for a far-left government fixated on the interests of the lower classes held little electoral weight. Some have oddly suggested Corbyn was electorally successful despite losing back-to-back general elections. The “sweetest of defeats” in 2017 was, regardless of how it is portrayed by some, a defeat, the result of the Conservative leadership’s incompetence more than anything else. Despite winning a surprising number of popular votes in 2019, due to the incompetence of all other parties, which made it an America-style two-party election between the Tories and Labour, the result was Labour’s worst since 1935. No matter how it is characterised, the far left has never managed to secure major democratic success in the UK.

France is often cited as a counterexample to the UK, where the far left has made more established electoral gains. The most notable of these is the National Popular Front, which is heavily influenced by France Unbowed (LFI) and became the French Parliament’s largest bloc in 2024. However, the alliance is assuredly uneasy, having previously formed under a different name, NUPES, before collapsing as a result of internal divisions. No majority has thus far been achieved, and given the deeply fractious and polarising nature of the LFI’s toxic leader, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who was found guilty of intimidation in 2019, it is unlikely that the National Popular Front will achieve significant policy impact. This is about as successful as any democratic radical left group is at present, something Mélenchon himself admitted in an interview with The Financial Times. If the most success the democratic radical left has managed to achieve is a shaky, majorityless alliance headed by an alleged anti-Semite, a political proletarian revolution is deeply improbable within the current political climate.

A shift in leftist political discourse surrounding class is required. The work of Marx is not simply outdated - it was essentially wrong. Formatted in such a manner that it has become, in and of itself, a self-verifying structure, it has failed to produce a proper understanding of class conflict. It has similarly failed to predict or trigger the downfall of capitalism, which has proven a deeply resilient and adaptable force. While this topic deserves an article of its own, it does frame the need for solutions. John Cassidy’s Capitalism and Its Critics suggests capitalism persists because “there remains no good alternative”, whilst simultaneously acknowledging the issues plaguing market systems. It argues that capitalist criticism, which often is a form of or relates to Marxism, provides utility in highlighting issues within market structures but fails to address these issues with practical solutions. Extending this argument to class, it can be said that Marxism has for centuries adequately emphasised the importance of class divisions, but has long failed to provide adequate policy direction to address these concerns.

This piece has heavily criticised Marxism; I intend to now provide a reasonable set of alternative ideals. Marxism has always succeeded in the theoretical sphere, and fallen demonstrably short in implementation, identifying issues without any realistic or desirable solutions to address them. I will now render a diverging theoretical foundation to address class-related issues, with the intent of penning a follow-up article to provide a more detailed, policy-oriented set of measures focused on its practical deployment.

The ramifications of class inequality remain notable in contemporary society. Wealth remains concentrated within the lineages of the upper classes, with the notion of equal opportunity crushed under the lower class’ endurance of comparatively subpar schooling, healthcare, and employment provision. Though social mobility has blurred class lines and somewhat negated these impacts, these issues persist. Yet, as this article has outlined, the workers do not rush to the nearest pitchfork salesman, intending to seize the assets of the wealthy, nor do they scurry to the ballot box to support the left’s ‘working class bastions’.

So, how should we address class inequality? We need to take a new approach. The working classes have rejected revolt and far-leftism despite the steadfast contemporary realities of the class structure. To enable social mobility, we need to help individuals climb the social ladder. You may be confused. That statement appears obvious. Read it again, but emphasise individuals. In reforging society to enable personal climbs up the social ladder, we can encourage intimate revolutions which serve as individual ascensions from subsistence origins.

When addressing class inequalities, equality of opportunity is a far more reasoned and applicable focus for policy construction than equality of outcome, which suppresses individual agency for the sake of state-enforced equality. That is not to say meritocracy is without issue, as it often creates an untouchable class through natural advantages. Old leftist strategies, which centre around direct wealth transfers, have failed because they are too closely aligned with equality of outcome. Meanwhile, neoliberal strategies have a destructive obsession with a meritocratic society. Both sides need to be coalesced (see also). The synthesis of these ideals, accepting government involvement in areas such as education and poverty reduction while maintaining meritocratic principles, can facilitate individual social ascensions regardless of class-at-birth with the embrace of a delicate degree of state-guided atomism. The construction of class solidarity, through revolutionary or political means, has been unsuccessful. To deconstruct the issues of class, or to deconstruct class itself, would be most effectively done by blurring class lines through the facilitation of complete social ascendancy, with working-class individuals unhindered by their origins as such.

A likely criticism is that some policy priorities, such as education, have been fraught with criticism over their limited impact on blurring class lines and enabling complete social mobility. I will address this topic further in my follow-up article, but in sum, governmental policy ought to be considered beyond a narrow scope of delivery. For example, education is not solely tertiary (or later) qualifications, yet contemporary labour markets operate as if this were the case. Broadening policy considerations could create a web of impacts, such as in employment law, to achieve more desirable outcomes. The state need not be large in scale, but delicate, precise, and broad yet thin in execution.

Marxists would criticise this outline, depicting social mobility as an illusory force intended to satiate the desire for outright emancipation. Social mobility in its true form, they would argue, would oppose the bourgeoisie's interests and thus would never be allowed. Rather than repeat the unfalsifiability argument, let’s assume the upper classes never go ‘against their interests’. Wider consideration of bourgeois interests in the capitalist economic system would suggest that, within the context of a particular state environment, embourgeoisement and complete social mobility do not go against upper-class interests, but fuel them. Rising median incomes are beneficial to the proletariat because they increase living standards for lower classes, creating cyclical benefits in increasing governmental income, facilitating more proficient state policy. At the same time, the upper classes can extract more surplus value, as there is more value to extract, from the internal state population. How is this facilitated? Globalisation, or more specifically, outsourcing. There is no need for each state to have a proletariat, as this is counterproductive to the bourgeoisie’s desire to maximise net value accumulation.

Contemporary Marxism has made significant ado about commodity chains in the Global South, one of the core challenges facing moral capitalism. Still, it highlights that, even within an accepted Marxist paradigm, their refutation of mobility as a coercive element of the state superstructure falls flat, given the globalised nature of capital. When operating under particular Marxist principles (to disprove its logic), the range of the required principles is broader than you might initially suspect. You are not only underpinned based on a specific counter-factual, but also Marxism’s core tenets of capitalism as an overtly corruptive force and the perpetual maximisation of value by the upper classes. These assumptions often underpin Marxist understandings of not only class but also their pseudo-scientific world-view, and these issues themselves deserve deeper questioning. Marxism is a set of foundational principles mired in their own self-verification, criticising the failings of capitalist structures while being unable to provide viable alternatives to them.

The enduring appeal of Marxism lies in its diagnosis of class, inequality, and the failings of market systems. Supposedly, consciousness of these issues will lead to an armed or political revolution that hasn’t, and never will, occur. The fantasy of class war has provided little practical utility other than highlighting the importance of class issues. Instead of this misguided focus, we ought to divert our efforts toward the empowerment of individual ascensions through true social mobility. The eradication of class comes not through a violent fist, but a truly meritocratic system built on a level-playing field, delicately constructed with a careful degree of state-guided atomism, particularly in areas of education, health, and poverty-reduction. If anyone could climb the social ladder, the age of class inequality would collapse, not with a hammer and sickle, but a new dawn of personal revolutions.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Wikimedia

Licence: public domain.

No image changes made.

.png)

Comments